Compassion: The Cornerstone of DEI

Recently, Ella and I were discussing various challenges that can crop up in organisations, particularly during the deep work required to meet ambitious DEI goals. During this conversation, we tried to identify the root causes of resistance; was it about fear of change, or fear of losing out? Was it about a lack of self-esteem in employees and leaders? Was it primarily because of a lack of understanding, or even misunderstandings about what DEI is for?

The more we hashed this out, the more certain I felt that the ultimate root of so many of these pushbacks is a lack of compassion - for oneself, and for others. As highlighted in last month’s blog post, individuals must learn to prioritise ‘compassion over comprehension’- you don’t need to understand someone’s experience to have a baseline level of compassion for them.

With further meditation on the topic of compassion, I realised that this is a wider issue - we seem to have forgotten to have compassion for humanity and for the planet too. With compassion - as with DEI - this isn’t confined to the realms of organisations. Yes, this is one arena where compassion and DEI work are desperately needed, but it goes far beyond the realm of work, DEI and compassion play a vital role in the systems and structures that shape our communities and societies.

In light of this, over the next few blog posts we will be exploring the concept of compassion across several different socio-cultural levels of society. We start first with self-compassion which is situated at the individual-level. The following blog posts will then work through compassion at the microsystem (i.e. the immediate social setting of an individual such as their workplace); and the macrosystem (i.e. the broader political and public institutions that govern our society).

So what does it mean to be compassionate?

I like to think I am a compassionate person that cares deeply about other people. I have a sneaky suspicion that many of us do - in fact generally individuals are motivated to see themselves and society in a positive light, particularly when it comes to issues of fairness and discrimination (Kraus et al., 2017). But does that mean I always spring into action to help other people? Do I always give money when I encounter an unhoused person for example? The answer is admittedly, no. Whilst failing to act does not diminish my empathy in these moments, it is however, at odds with the definition of compassion.

Compassion can be both a trait-like skill, and an emotional state that arises when people observe the suffering of others, and are motivated to reduce that suffering (Goetz, et al., 2010). This means doing something tangible to help others. Action is therefore the central piece of compassion that differentiates it from other similar concepts such as empathy, sympathy, or kindness.

From a trait perspective research suggests that compassion is a ‘character strength’ (i.e. a positive characteristic that is morally valued throughout the world; Ruch et al., 2021). Pioneering work (from Dr Chris Peterson and Dr Martin Seligman and his team of 55 scientists, who analysed hundreds of historical texts) found that almost all of the major world religions recognise and actively advocate for compassion in their teachings (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Even ancient philosophers such as Confucius, Buddha, and Lao Tzu, observed compassion as a fundamental human value.

So compassion has long been treasured from a moral standpoint, not least because it is critical to building and maintaining high quality relationships and high functioning societies (Gilbert, 2021). The benefits of practising compassion abound - for both the giver and the receiver/s. For instance, compassion increases one’s mental health, including boosting self-esteem (Neff, 2011), psychological wellbeing, and subjective happiness (McKay & Walker, 2021), whilst also buffering against stress and mental illness (Gilbert, 2005; 2010).

Yet if compassion is so highly valued, and has such wide-sweeping benefits, why does it feel like we are struggling to lead with more compassion in our lives? The answer may be closer to home than we realise…

The reality is, compassion starts with the self.

I have two dear friends, one who radiates compassion, and one who struggles with it. The key difference between the two, is that the former friend is deeply self-compassionate, is kind and gentle on themself and this, in turn, amplifies outwards to others; whilst the latter is hard on themself, critical and judgemental and this too can radiate outwards to others. Recall the familiar phrase “one can’t pour from an empty cup.” This speaks beautifully to the concept of self-compassion. How can we extend compassion outwards to others if we cannot first extend compassion to ourselves? It is the same principle that we see promoted on the safety cards of aircrafts, put your own oxygen mask on first before helping others with theirs.

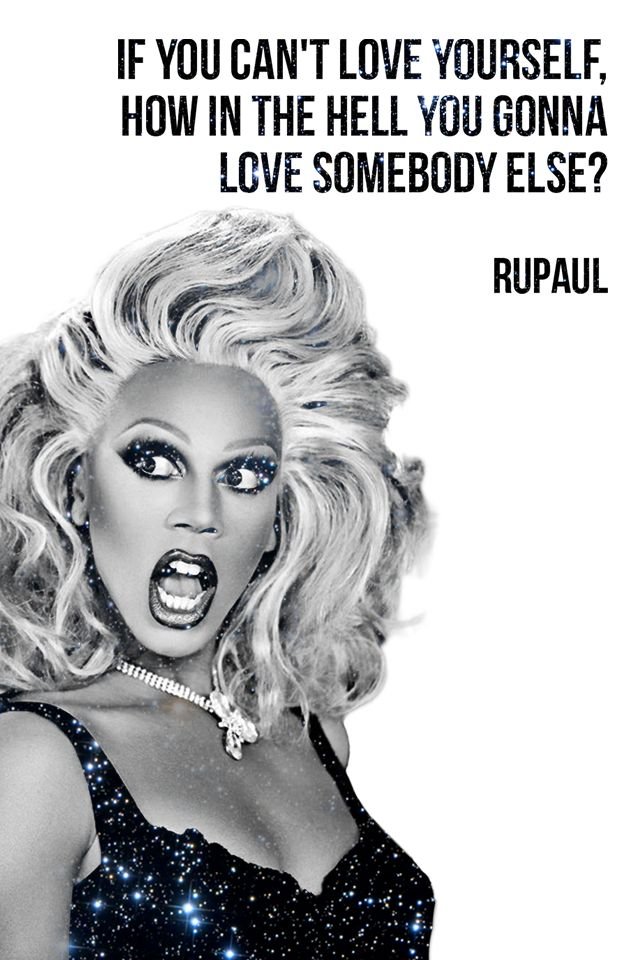

Ru Paul gets right to the heart of the issue by talking about the need for self-compassion.

Dr Kristin Neff (2003) conceptualises self-compassion as the ability to give yourself the same love, support, and non-judgement that you would extend to another. Much like compassion more broadly, self-compassion comprises 3 elements:

Kindness

Being kind and non-judgmental towards the self rather than self-criticalMindfulness

Being able to hold difficult feelings in mindful awareness rather than becoming overwhelmed by themCommon Humanity

Viewing one's suffering as part of the human condition rather than as an isolating experience

When we are able to engage with self-compassion (often through mindfulness or meditation) we can expect to enhance our wellbeing and motivations to act in the best interests of others (Neff, 2023). Yet many of us fail to engage with self-compassion. We can easily mistake self-compassion for self-indulgence or selfishness, or even worse for weakness. These myths are disastrous, because they prevent us from putting on our oxygen masks at all.

Make it stand out

Last summer, footballer Dele Alli bravely opened up about his childhood trauma and how a lack of self-compassion had impacted his life on and off the pitch.

In reality, self-compassion might not come naturally to everyone, for many it may require more of a concerted effort. It is likely to be uncomfortable to engage with at first, particularly given the fact that we live in a world that promotes self-derision and may be doubly hard for those living with trauma, or those who weren’t shown unconditional love as a child. Despite this, self-compassion can be developed. Like any other muscle, it will grow if only we endeavour to flex it.

Now for the good news: there are several tried and tested methods for boosting your ‘orientation’ towards compassion (Feldman & Kuyken, 2011).

For those where self-compassion is more arduous, compassion focused therapy can be particularly powerful (Gilbert, 2010). In this therapeutic practice people are given psychoeducation on the physiological systems that underpin compassion (i.e. threat focused protection, reward seeking, contentment and openness). Fostering compassion via soothing breathing, and safe space imagery can help to regulate emotions that we fear, and give us the courage to engage with those emotions.

Outside the realms of therapy, we can work on self-compassion as part of a guided group programme, and even unassisted in the comfort of our own home via mindfulness or meditation. One example is the mindful self-compassion intervention developed by Neff and Germer (2013). This is a 8-week group programme that aims to increase one’s levels of self-compassion. Each session is 2 hours and includes meditation practices (e.g. loving-kindness meditation) and exercises, as well as education on self-compassion. Topics covered include the negativity bias, how to develop your own compassionate voice, managing difficult emotions, and identifying core values.

If, like me, the thought of meditating makes your bum clench, an even easier pathway to self-compassion is by practising gratitude (Voci et al., 2019). Gratitude is straightforward and doesn’t require planning or a significant time investment. Simply spend 15 minutes a day considering the things you are grateful for in your life - this could be the people in your life, the things your body can do, small joys such as a nice cup of tea. Doing so can not only open the gates to building self-compassion as it provides you with a space to be grateful for yourself, but can improve your general wellbeing too (Lai & O’Carroll, 2017).

It is important to acknowledge that, when embarking on this journey of self-compassion, we must be gentle to ourselves; Rome after all was not built in a day, and nor will your self-compassion reservoir suddenly overflow. Be patient and be consistent.

If more leaders were able to build deep self-compassion, imagine how drastically our workplaces would change? As it stands, the efforts of DEI workers face significant opposition, often from leaders who are unable to give themselves some grace when receiving criticism of their workplace and how it operates. A key baseline of self-compassion - the acknowledgement and acceptance that we are flawed individuals who make mistakes - would go a long way to creating openness and receptivity to change. And we will all make mistakes when it comes to DEI, but can we do so with loving kindness to ourselves?

As author, poet and activist Sonya Renee Taylor points out in The Body is not an Apology:

“The world benefits when we love ourselves unapologetically.”

If we want to enact radical, transformative change in our organisations, and in society more broadly, we need to first start engaging in radical self-compassion.

Further Reading

Check out this book by Dr Kirstin Neff

Check out this book by Sonya Renee Taylor

The Body Is Not an Apology

Check out this TEDx Talk - Dr Kirstin Neff

References

Feldman, C., & Kuyken, W. (2011). Compassion in the landscape of suffering. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 143-155.

Gilbert, P. (2005). Compassion: Conceptualisations, Research and Use in Psychotherapy. Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2010). An introduction to compassion focused therapy in cognitive behavior therapy. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(2), 97-112.

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 6–41.

Gilbert, P. (2021). Creating a compassionate world: Addressing the conflicts between sharing and caring versus controlling and holding evolved strategies. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 582090.

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351-374.

Kraus, M. W., Rucker, J. M., & Richeson, J. A. (2017). Americans misperceive racial economic equality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(39), 10324-10331.

Lai, S. T., & O’Carroll, R. E. (2017). ‘The Three Good Things’–The effects of gratitude practice on wellbeing: A randomised controlled trial. Health Psychology Update, 26(1), 10-18.

McKay, T., & Walker, B. R. (2021). Mindfulness, self-compassion and wellbeing. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110412.

Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85-101.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self‐compassion, self‐esteem, and well‐being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 1-12.

Neff, K. D. (2023). Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual review of psychology, 74, 193-218.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self‐compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28-44.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Vol. 1). Oxford university press.

Ruch, W., Gander, F., Wagner, L., & Giuliani, F. (2021). The structure of character: On the relationships between character strengths and virtues. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(1), 116-128.

Voci, A., Veneziani, C. A., & Fuochi, G. (2019). Relating mindfulness, heartfulness, and psychological well-being: The role of self-compassion and gratitude. Mindfulness, 10(2), 339-351.